Megan Farnel

Occupying/The Last Internet Cafe in Jakarta

“Four people died at the Freeport protests.”

“I know, I tweeted about it.” The instant I say it, in a tone that’s more than slightly defensive, I know it’s a mistake, that it will further highlight the growing division between us. The headlights on a passing car reflect briefly off my phone perched on the table as if to support her unspoken accusation; several of us attending school together have followed #OccupyJK on Twitter or liked the Facebook group, but her boyfriend is the only one any of us know who has been daring enough to attend one of the rallies in person. If we was there today, and if her breathless tone in announcing the shootings that have already made local and international headlines are any indication it’s almost certain that he was, she will no doubt claim the right by association to become the official voice of the ‘real’ Occupy movement in Indonesia. My tweet, despite being retweeted by over three hundred people and groups (including #OWS, for the first time), exists in the shadow Occupation, matters less than even her tenuous connection to the bodies aligned in the streets standing together, dying together. When they have children one day, she will proudly point to Freeport from the car, or on a map, telling them about how their brave Father joined the other heroic anticapitalist crusaders, how he stood up and made a difference while others only Tweeted about it.

I wish I could show her my Occupy.

***

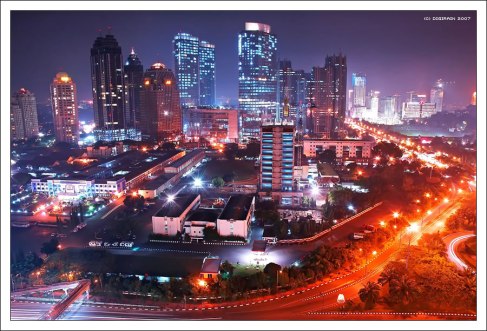

Upset by our meeting, I leave dinner earlier than intended and walk home alone via a slightly intimidating back road I normally avoid. It takes me past one of the Internet cafes; though it had been a constant mainstay of my childhood, I’m slightly surprised to find it’s still open. Many of them in Jakarta have closed in the past several years, succumbing to the power and convenience afforded to us by mobile technology.

Other than the owner, only one person is inside, a vaguely familiar young man I have passed in the neighbourhood before. He is seated at a computer as far from the proprietor as he can get, back hunched over the screen as if to shield it. Positive he’s watching porn (despite the multiple signs promising dire consequences), I pause by the window and peer in, plotting to bang on the glass just when things get interesting to remind him that if he wants to watch porn in public, he should be less worried by the sole middle-aged man in the corner than by the fact that his screen is facing a wall of windows.

Just as his screen starts to become distinguishable, I turn away again, and indulge in a fantasy instead: what if he has Occupy Indonesia’s Facebook open? I would hesitate for what would feel like a long time, debating going inside and introducing myself, or tapping quietly on the window and pulling the page open on my phone. I imagine the secret smile we’d share, the warmth of open solidarity unmediated by a screen. For an insane moment, I would even consider going back to the restaurant and dragging her here; proof, at last, of my own connectedness, my own relevance to the movement.

But yet, I can’t help but be suspicious, too, of that desire. Why do I need this one man, this small, dingy space to validate everything I’ve felt and done in the past several months? It’s been so much bigger than this, so much bigger than him.

***

I pretend to remain oblivious, because the secret is half the fun at their age, but I know what the children who come in here call me: the oldest Indonesian man on the Internet. The truth is I’m not that old, but the divide that separates the 20% of the country that use Internet from the 80% who can’t is not only based on wealth; it is based heavily on age. The Internet is primarily a gathering space for the young.

I make use of the Internet, and have done so for many years, but it wasn’t an abiding love for the technology that caused my to open an Internet cafe. To me, then, the excitement of the Internet was so bounded up with the fervor regarding our newfound democracy that it seemed natural to assume that Internet cafes would become the primary social spaces for meetings, debate and meaningful change. The new forum.

I wasn’t entirely wrong; they were, for at least a while. Kids with and without their parent’s permission to step inside would come in, usually with a friend or three, and under the guise of ensuring that they weren’t watching pornography, I would wander amongst them as subtly as I could, gaining a sense of the various social issues in Jakarta they were speaking and typing about. Some of them were much braver online, of course; others spoke in heated, passionate whispers to their friends but barely touched the computer in front of them, as if the access they were paying me for was not so much to the Internet as it was to a safe space, away from the eyes of parents and teachers, to say what was really on their minds.

The arrival of mobile phones changed all this. For a while I tried to remain relevant by adding various games to the systems. Then I lowered prices (which had already been the lowest on the street). But really, how can I blame them? I, too, have a Blackberry, and given the choice between using that or trekking to what can be a fairly dangerous street at night (the location was the only one I could afford, and by the time I had earned enough to move, it was too late), I would hardly opt for the latter by choice.

They say there are to be 40, 000 people showing up tomorrow to protest recent price hikes on petroleum. I glance over at the sole man currently using one of the computers, fantasizing for a moment that he’s involved as one of the organizers, that he’s excitedly checking his Facebook or his Twitter to find out if any more people have committed to attend. Even if he is, though, he’ll be gone when his time expires in a matter of minutes, and when I go to the rally tomorrow, likelihood is that I’ll never see him, never find that trace that leads back to the last Internet cafe in Jakarta.